When I was a first-year teacher in the fall of 1992, I really had no idea exactly what I was getting into. Sure, I had earned my teaching credential and completed student teaching, but I had never had my own classroom and five classes full of students for an entire year. I was 23 years old and didn’t know much about Long Beach Poly High School where I would be teaching English and Speech.

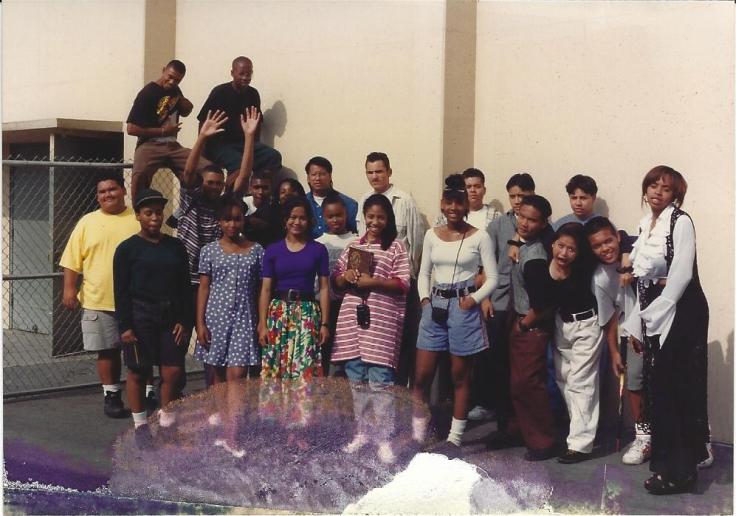

Long Beach Poly is a giant school in a giant district. At that time there were approximately 4,000 students comprised of those enrolled in a district honors magnet program (referred to as PACE), as well as kids from the neighborhood. The students in the PACE program were clustered together in most of their classes, away from the rest of the student body. The teachers seemed to be “clustered,” too, based on if they taught in the PACE program or if they taught . . . the rest of the student body. It’s easy for students . . . and first-year teachers to get lost in such a large school.

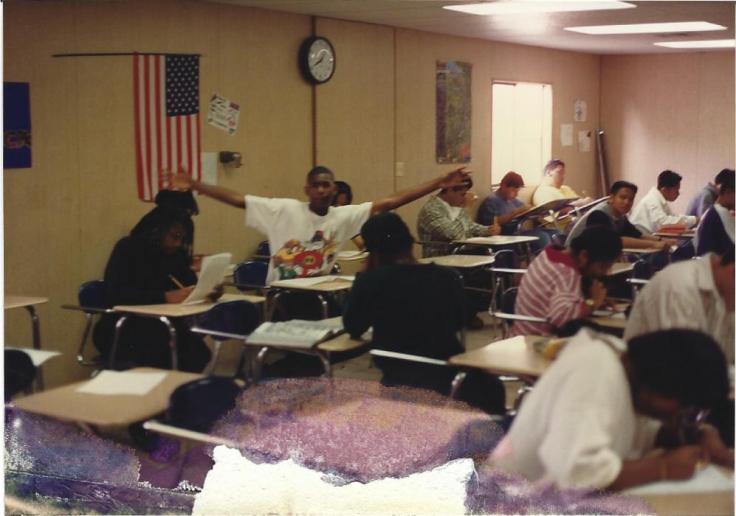

As a first-year teacher, my contract stipulated that I must be given my own classroom (while other teachers often had to share several different classrooms). I was assigned to teach in a brand-new bungalow. This sounds great, but it was on the outskirts of campus and I wasn’t even given a key to my room until lunchtime the first day of school. So, I didn’t have the opportunity to set up my room before school started and I had to find a custodian to open my room for me before school on the first day. I also didn’t have electricity for two weeks, which meant teaching in the dark . . . literally and figuratively. There didn’t seem to be much of a sense of urgency from anyone in providing electricity in my room. I didn’t really know who to go to for help. Eventually, I went to one of the three assistant principals to again ask about power.

It was in her office that another teacher asked if I had third period conference because he wanted to know if he could teach his third period class in my room. He was currently assigned to teach his class in the diesel mechanics room, which clearly was not ideal. Not knowing any better, I said sure, he could use my room. I didn’t know him, but then again, I didn’t really know anyone. Only later did I realize that I would no longer have that time to work quietly in my own classroom because he would be there with a room full of students.

This arrangement turned out to be more significant than I ever could have realized.

Though I was tempted to leave the room during my conference period, so this teacher could have his own space, I ended up staying more days than not. At first I couldn’t believe how he spoke to students. He was direct, funny, honest. He poked fun at his students . . . all of them, in a way that showed he really knew them. And, they responded. They bantered with him and hung on his every word. He did not interact with students the way my master teachers had modeled. I began to re-think how I spoke with students. Maybe I could be more myself rather than playing the role of a teacher.

Not only did I see another way of behaving like a teacher, but this man also shared lesson plans and strategies, offered advice, and just encouraged me to hang in there. Teaching can be very isolating and that first year is especially tough. Most teachers enter the profession with high hopes and altruistic intentions. But, it is lonely, exhausting work, and though there are successes, there are also many, many failures. Sharing a room for even one period changed my perspective of the teacher I was to become.

Years later, at another school, in another district I was commuting 30 minutes to work. (In Southern California we measure distance in time. The drive was about 11 miles and could take from 20 minutes, if I left at 6:30am, to an hour, going home on a Friday.) Eventually, I started carpooling with another English teacher. Not long after that my husband (also an English teacher) was hired at the same school, so the three of us carpooled. Carol taught at the same school for going on 30 years and I had about five years of teaching under my belt at the time. The conversations we had to and from school for many years did more to educate me about teaching than any class or formal professional development ever did. We would talk about what our plans had been for our students and debrief how things went. We celebrated successes, and reflected on failures.

And, boy were there failures.

Teaching up to 175 students, five days a week, for 180 days provides ample opportunity for failure. Though Carol was a “seasoned veteran” teacher, she continued to try to new things and adjust her approach each year and for each class. She was not some experienced teacher who merely pulled out a binder and turned to the handout for day 47. What was great was hearing her talk about developing some new project or activity, only to have it fail miserably. Sometimes it would work great with one class, but not another. (We all know how classes have different “personalities.”) It was encouraging to know that someone with far more experience than me still failed–and, more importantly, re-grouped, adjusted, and returned to teach (and possibly fail again) the next day. We would laugh about what went wrong and how we adjusted or admitted to students that something didn’t go as planned. I thought by this time, certainly she would have it all down pat. But, that is the thing with teaching. It doesn’t work that way. There is always a human element and that element is organic, fluid, and unpredictable. And there are up to 35 of those elements . . . in every class.

These two teachers fell into my life and forever altered how I approach working with students. But, I’ve had other brief interactions that impacted me, too. One year when our school was under construction, a math teacher asked to use my room during my conference period because she was in a bungalow and the AC was out. (If you’ve ever taught in one of these “portable” bungalows on a hot day with no AC, you understand why this is necessary.) I didn’t know this teacher at all. I knew her name, that she taught math, and that students said she was tough. I had so much fun watching her teach that day. I hadn’t taken a math class since my freshman year of college, and the pedagogy has changed a lot since then. But, it wasn’t really the math that I revisited that day that sticks with me. This teacher really knew her students and really wanted them to succeed. She predicted who would be “off-task” and brought them back. And, she was funny. She wasn’t “hard,” she had high expectations and helped her students meet them. She and I had a connection after that day that we wasn’t there before.

In my 23 years teaching high school, I’ve spent countless hours on professional development–conferences I requested to attend, conferences I was required to attend, district inservices and training, school site inservices and training, workshops, presentations, classes. Sure, some of these offered specific materials, projects, activities, approaches, and ideas that I could use in my classroom. (Sadly, most of them were painful wastes of time.) But, watching others teach, getting to know them, chatting with other teachers about ideas, struggles, successes and failures did far more to help me become a better teacher than any inservice or workshop ever did. I connected with these adults and respected them. I “stole” ideas and strategies and made them my own. I didn’t try to emulate or imitate them, but I found my own style and approach. Oh, and that teacher at Long Beach Poly who used my room . . . we’ve been married for 21 years. And though we don’t teach at the same school anymore, he still fails, but keeps showing up every day. We still tell stories and laugh.

Leave a comment